Australia Day

Silhouette portraiture became popular during the mid-eighteenth century, hailed as a more affordable alternative to ivory portrait miniatures. Yet this new portraiture emerged alongside a revival in physiognomy, the ancient pseudo-scientific field which asserted that one’s appearance, especially facial features, might correspond to particular and innate personality traits. Suited to documenting features in a cold, ‘objective’ manner, the silhouette was easily absorbed by this field, and became forever entangled with emergent techniques in scientific racism and criminology. Today, the profile is essentially synonymous with the mugshot. Physiognomy, meanwhile, is undergoing yet another revival within the context of computer vision and machine learning.

The interior of a silhouette is of course entirely featureless, the figure shadowed by a hot white background. It withholds information, and is therefore error prone. As a tool of documentation it is therefore a paradox, anatomically precise, yet defined by significant blind spots. The viewer is drawn to the limited clues which might reveal something of the subject, dress, tension and posture, profile. Which details do we dwell on, and which do we neglect? Perhaps more importantly, what is being withheld by the silhouette, by those tracts of canvas which do not possess data? How is it that these absences manage to contribute? At this point we might be reminded of Quilty's long engagement with the Rorschach test. Hermann Rorschach developed his eponymous ink blot tests to draw out the patient’s pure subjectivity. His tests did so by being randomised, containing no reference to the actual world, no pre-existing information or meaning. An image from nowhere which would capture vulnerable first impressions. The tests worked (so he claimed) precisely because they created empty space.

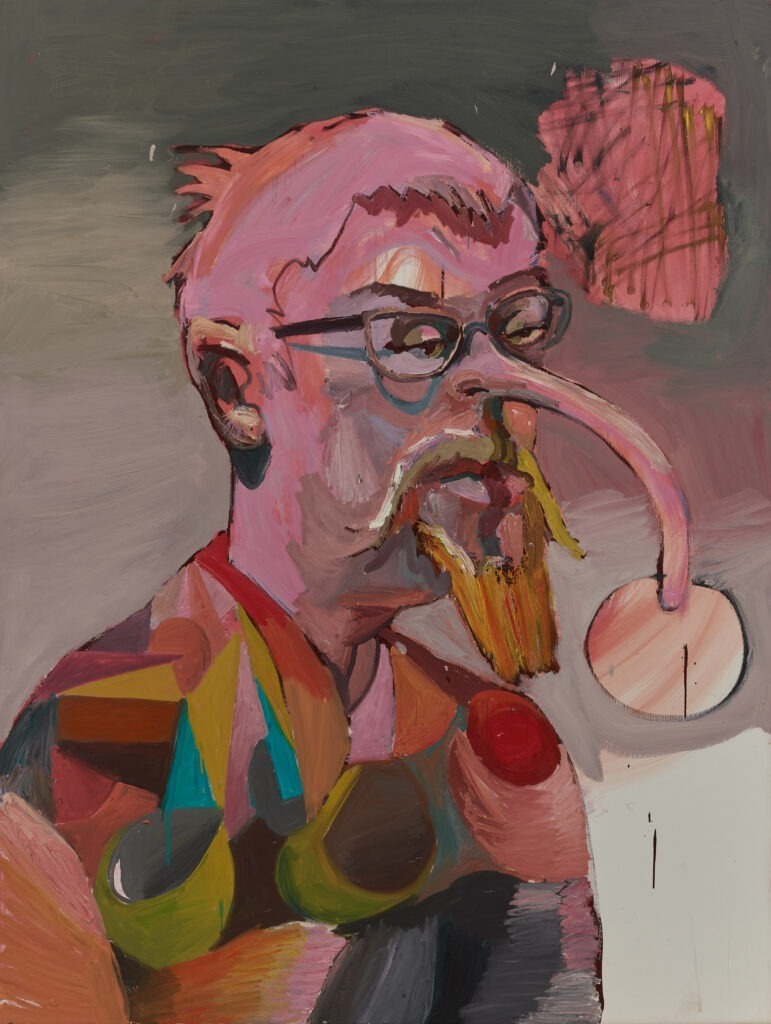

In the silhouette and Rorschach, Ben is clearly preoccupied with the optical sciences of human psychology and cognition. Tests, techniques, disciplines and discredited pseudo-sciences which have all too often wielded immense power over individuals and populations. In Shadowed, he is swimming further into the unconscious. While Quilty has different intentions and ideas to the physiognomist, they both deal in faces, and pieces of faces. Here, the mouth in particular stands out. Buckteeth, fangs and mandibles are rendered in gouache and ink on paper, charcoal, graphite and oil on canvas. They are deconstructed and cruelly reassembled, he is inventing new expressions, conditions and yes, personalities.

Perhaps the central question then, in Shadowed, is the articulation of human difference, whether that be in our mental states or in our appearance. The vacuums and shadows generated by these processes are utilized fully, expressive tools and not accessories to form. Meanwhile, The Daughter, a familiar face for the artist, hums with a sickly incandescence, and might have belonged in Laloux’s Fantastic Planet (1973). In Facing up a bald head sits in the gloom like a lost asteroid, stretched, and cold.

A stunning art book of Quilty's most recent collection of paintings from his series 'Free Fall'

‘This series, titled "Free Fall", was heavily influenced by American realist George Bellows’ early 20th-century boxing series. Where Bellows looked to boxing, the premier bloodsport of his age, Quilty has turned to the modern phenomenon of the Ultimate Fighting Championships (UFC). Looking back on Quilty’s work in recent years, his ongoing exploration of heavily abstracted, tortured anatomies, perhaps it was inevitable these figures, or their kin, would end up in a fighting pit, aka the ‘UFC Octagon’. Crucially, while studying Bellows, Quilty revisited the iconic images taken by photojournalist (and cousin) Andrew Quilty of the 2005 Cronulla riots. Here, the beach and the Octagon are corresponding zones, symbolically potent places steeped in friction, violence and ritual.’ – from the Foreword by Milena Stojanovska

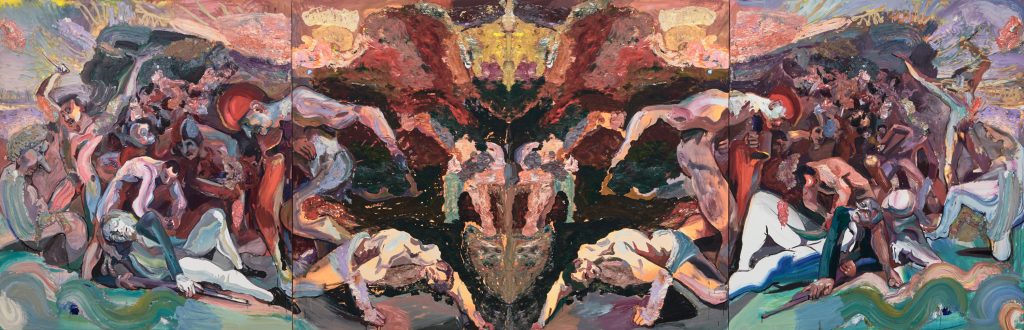

The underlying structure of each of these paintings is formed by Rorschach images. Rorschachs were originally meaningless mirrored images used in clinical psychiatry as an aid in the diagnosis of schizophrenia; the patient would offer an interpretation of the image which itself would be analysed and interpreted by the psychiatrist. With the diagnostic outcome significantly dependent on the interpretative biases and prejudices of the practitioner, there are conflicting views on its efficacy and accuracy.

However, interpretative instability is a potent lens through which to consider history. Specifically, the common rift between the version of history moulded and proliferated by the powerful, and the often involuntarily subterranean versions of events according to the disenfranchised and exploited. History turns out to be increasingly provisional as we widen the aperture to include stories and angles that have been deprived of a platform by the dominant culture; fixed history gives way to fresh and complicated waters as the massaged renditions created to serve and preserve the purposes of contemporary power are wrenched from their monologic state into dialogue.

Ben Quilty is preoccupied with this dialogue and its generative potential as much as with the painful consequences of relegating atrocities to the tidy western notion of an historical past. In his work authoritative History is disturbed and revivified and the paintings are often an uneasy amalgam of conflicting accounts and viewpoints. They embody the reckoning he faces again and again with his ancestral connection to the violence of the colonisers and the oppressors; the history in which he is implicated.

Alien, Cooks death, after Zoffany 2022, as the title suggests is based on Johann Zoffany’s painting The Death of Captain James Cook, 1795. Zoffany’s theatrical depiction is itself derived from the story of Cook’s death at Kealakekua bay Hawaii in 1779 that proliferated in the West in the intervening years in the form of pictures, plays and written accounts. The commemorative painting appears to portray Cook as a martyr, captured in the moment of surprised and somewhat bewildered recognition of his own stabbing. The Hawaiians are depicted decisively as the aggressors with any sign of British wrongdoing and malice omitted from the painting.

‘Alien ’Captain James Cook, bearing gifts of Venereal disease and Tuberculosis from foreign lands was initially mistaken by the Hawaiians to be the god Lono and welcomed with reverence. He had coincidentally arrived at the time the deity was due and his ship’s mast and white sails are said to

have resembled the wood and white bark-cloth associated with the fertility god. However, suspicion about Cook’s godliness swiftly evolved into hostility following Cook’s sudden (un- godlike) return to the island due to storm damage incurred by the ship.

The action of Alien, Cooks death, after Zoffany emanates from a direct mirroring along the central axis. The split widens both visually and metaphorically as divergent versions of the one history painting spread left and right, our eye tracing a compositional loop back to the centre and out again until it feels as if we are caught up in the turbulence of two immense flapping wings. This dynamism is echoed in the mutations occurring in the details; figures morph into a new set of players. Cook’s face on either side is supplanted — on the left by that of Christ derived from Rubens’ painting The entombment, and Quilty’s father on the right with a comic Pinocchio nose. The heroic Captain Cook conveyed by Zoffany, Captain Cook the Martyr slayed ruthlessly by the natives, breaks like a great wave upon the rocks and in the tumult surfaces questions of authority, narrative power, the legacy of colonisation and white man’s attitude towards difference.