27 October – 21 November 2020

Quilty makes no fuss in selecting his objects, leaving the studio in search of ‘beauty’ was neither responsible, or, as it turns out, necessary. Multi-vitamins, disinfectant, clamps, wine glasses and pumpkins are gathered to create disjointed clusters. These commonplace markers connect his experience of isolation with many of our own. Quilty creates amusing rhythms in these undulating compositions, with characteristic blocks of colour.

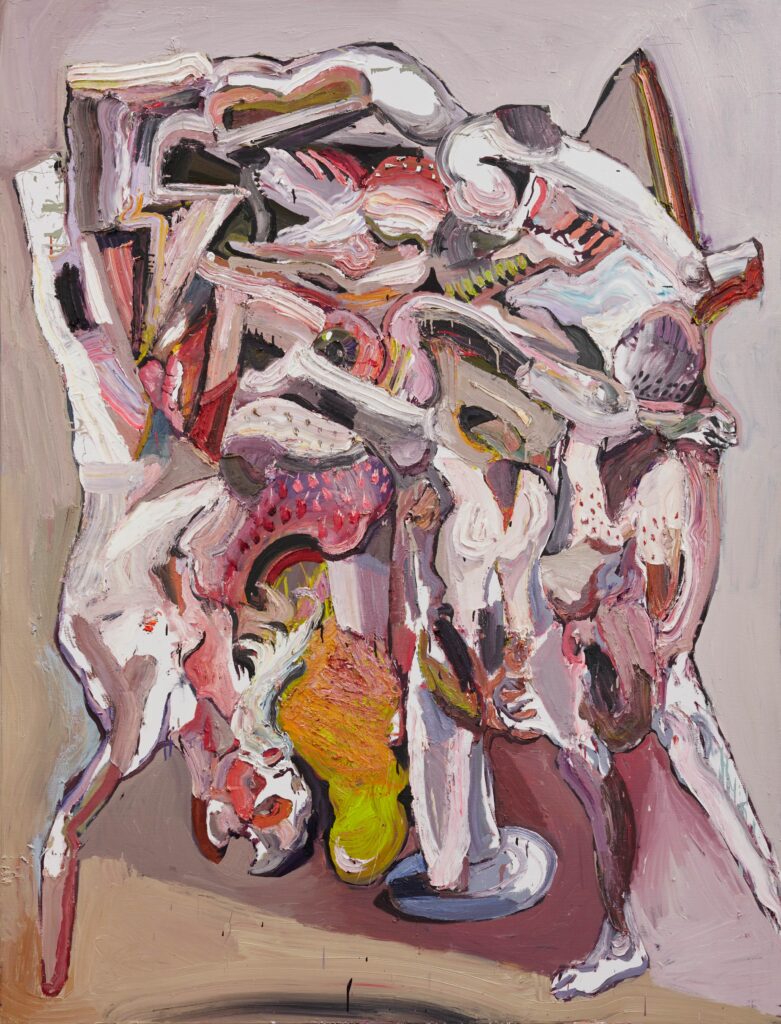

In a work titled The Last Supper, 2016, Quilty painted a feverish image in the aftermath of the US presidential election. The human subjects here, dead or dying, are centrepiece in the newest iterations of what we might call the banquet series. Is this a pseudo-cannibalistic feast, autopsy or vivisection? These are an unsettling yet fine reimagining of 14th century deathbed scenes come Jan van Calcar’s eccentric human anatomies.

Beginning in the 16th century, in a time of great mercantile wealth and constant military conflict, a dark style of still- life painting emerged in Europe. Known as vanitas, the paintings were lush with symbolism and sought to emphasise the impermanence of life, the futility of earthly pleasure, and the pointlessness of pursuing power and wealth. It was the human skull which most famously came to embody the central themes of this style. Quilty places skulls with mass produced, mundane products of modernity. Glen 20 and multi-vitamins are particularly emotive, reflecting the highly commercialised, sensationalistic ideas of human health and urban sanitation in the modern world. Depicted in such a manner, they are gifted novel symbolic power.

Words by Milena Stojanovska, 2020

ABOUT THE ARTIST

In 2019 the first major survey exhibition of Quilty's work was presented by the Art Gallery of South Australia. Curated by Lisa Slade, the exhibition QUILTY toured to the Art Gallery of NSW and QAGOMA. Quilty has been a finalist in the prestigious Wynne and Archibald prizes and won the Doug Moran National Portrait Prize in 2009 and the Archibald Prize in 2011 with his portrait of artist, Margaret Olley. Also in 2011, Quilty travelled to Afghanistan as an official war artist with The Australian War Memorial. He was invited by World Vision Australia to travel to Greece, Serbia and Lebanon with author, Richard Flanagan, to witness firsthand the international refugee crisis in 2016. His work is represented in numerous major public, corporate and private collections including the National Gallery of Australia, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Art Gallery of South Australia, National Gallery of Victoria and QAGOMA.

“Nellies Glen has been a favourite gathering place for locals for over 150 years. With beautiful ferns and moss covered rocks it provides a quiet haven for swimming or just relaxing in the cool, quiet surrounds.” – Budderoo National Park information plaque.

Through Quilty’s ominous and heterogeneous approach in 150 years each work invites us to participate in a critical discussion. The same Quilty who explored the spiritual hollowness of contemporary masculinity in paintings of passed-out mates is present here, yet these themes are refracted through the decades since, through experience, a global and pervasive uncertainty, and a tangible level of disillusionment. In an age of authoritarian revival, Quilty’s decades-long interrogation of masculinity is gaining momentum.

Recently dubbed a ‘critical citizen’ by curator Lisa Slade, Quilty’s new work at Tolarno more explicitly depicts a self-critical citizen. In this case Self may not necessarily connote oneself, but one’s milieu, an individual splattered, dispersed throughout their socio-cultural plane. The artist – as well as a few family members and friends – are present in the landscape of the Rorschach, in the abstract works, and of course in Santa himself.

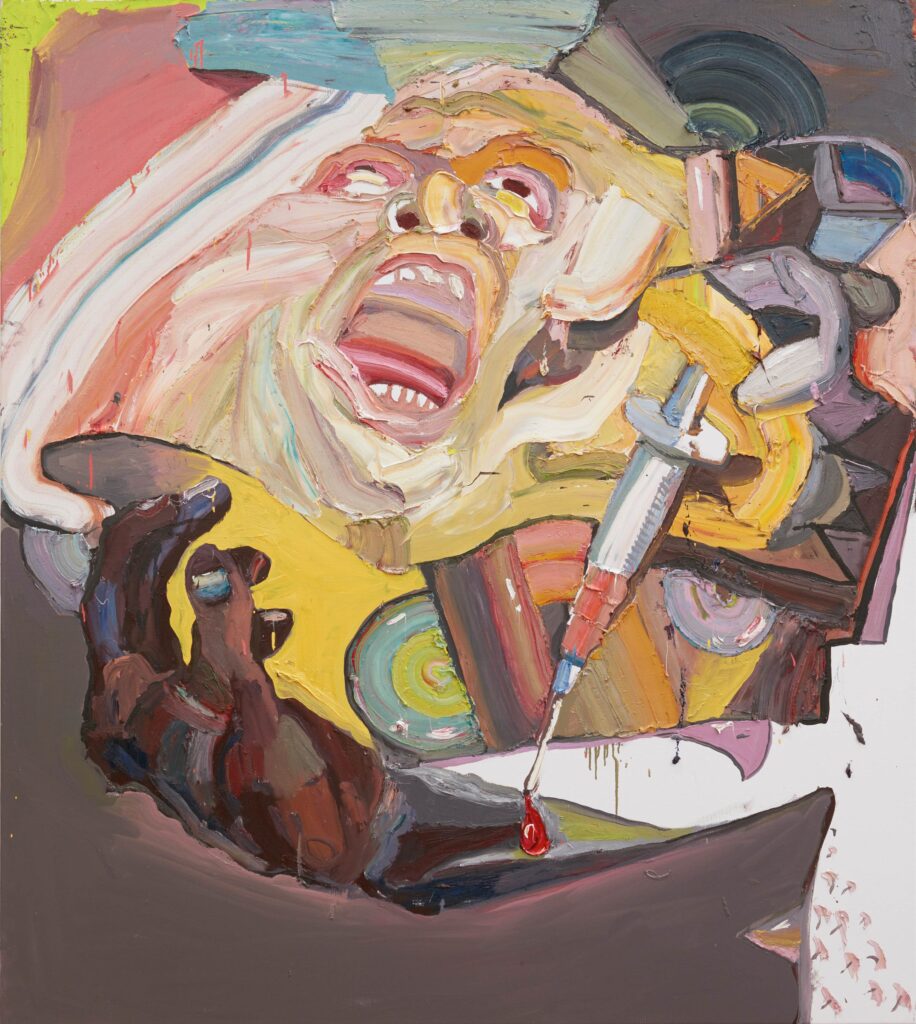

The first iteration of Santa, which appeared in 2018, was perhaps best confirmed by the response they elicited from media commentators. The depiction of Santa drunk and urinating in a pot plant was deemed iconoclastic enough for right-wing commentator Andrew Bolt to assert that “the new racism” had been “rubbed in his face”. Quilty chose Santa because he is (like the artist) a straight white male, but it is clear the series is as much about consumerism as it is about whiteness. Santa teaches us to be good, not for the sake of goodness, but solely in the pursuit of material reward. His dishevelled presentation in these paintings reflects this crass and deeply cynical ethos. With his imposing, bloated head, Quilty’s Santa carries something of the famous facade on Mussolini’s headquarters, or Big Brother. He does of course, surveil all year round.

Santa reminds us of something that has largely been overlooked in Quilty’s work, that given the right subject matter, it can actually be funny. That a satire of a fictional children’s character, who essentially serves no role in society, was received as a serious attack on Western values, or patriarchy, perhaps illustrates the impotency of those values more than anything else.

The knotted forms in The Interior and The Ludicrous Mode are an athletic accomplishment, tying together a myriad of elements, led by wielding brushstrokes. As always in his work, the blank sections of canvas are used economically, surrounded by decisive, thick slatherings of oil paint. Grey is prominently featured, often as a backdrop for vibrant bursts of red, pink and orange. In works such as At the bottom of the fish tank, colour and form work rhythmically, a choreography of our focus, dragged through the tangled composition. That is the tension here,

that which tells us where to look and in what rough order, and that which simultaneously resists literal interpretation.

In Self-Portrait, about my Brother, the thematic issues explored elsewhere find a sounding board. A component or subtext in other works, the artist appears fully here. The palette used in the figure is curiously matched by the background. But rather than melting away as one might expect, he is lifted from the canvas. A few streaks of blue pull the character forward with a bizarre confidence.

150 Year, Rorschach paints a landscape Quilty and his son Joe found during a bushwalk in the Southern Highlands. A plaque on site (quoted above) suggests the waterhole has only been visited and enjoyed for 150 years. 150 Year, Rorschach does not depict a specific tale of atrocity, marking it apart from a number of his earlier trademark works. The specific location is secondary to the beings which animate it, and what they have come to represent. A cat, toad, fox and goat adorn this site. The century before federation saw a long period of ‘Acclimatisation’, when all native species were vilified by white colonisers and the beasts of Europe were promoted, consciously seeded into the landscape. A systemic project one historian has wryly described as ‘ecological cringe’. The introduced species of course do not act alone, a Rodin sculpture is mimicked, dancing jubilantly with the pests, as thick in the Western canon as he is here, surrounded by suctioned paint.

The huge mirror opens itself up to us, peeling itself from the centre and the inside, drawing us deeply into the blasted Australian landscapes which in this time hang on the precipice. These fractured ecologies are addressed with the textural complexity of the Rorschach, the miniature waves hanging in their thousands.

The sign at Nellies Glen, like so many others peppered throughout the Australian landscape, is a mechanism of erasure. It illustrates how effortless this forgetting, both intentional and subconscious, has become. The vast painting is therefore an invitation to better, more attentive ways of looking.

– Milena Stojanovska

A celebration of the last two decades of work from Australian artist Ben Quilty, to coincide with a major retrospective of his work. With a Foreword by Richard Flanagan.

Ben Quilty has worked across a range of media including drawing, photography, sculpture, installation and film. His works often respond to social and political events, from the current global refugee crisis to the complex social history of Australia; he is constantly critiquing notions of identity, patriotism and male rites of passage.

Quilty is a past winner of the Archibald Prize for portraiture, the National Self-portrait prize, and the Doug Moran National Portrait Prize. This rich and comprehensive collection of his work from the past two decades is accompanied by essays from Lisa Slade and Justin Paton.